"In his irrepressible way, and with his distinctive voice, Madden left an imprint on the sport on par with titans like George Halas, Paul Brown and his coaching idol, Vince Lombardi. Madden’s influence, steeped in Everyman sensibilities and studded with wild gesticulations and paroxysms of onomatopoeia — wham! doink! whoosh! — made the N.F.L. more interesting, more relevant and more fun for over 40 years."

...

"Rising to prominence in an era of football commentating that hewed mostly toward a conservative, fairly straightforward approach, Madden’s accessible parsing of X’s and O’s added nuance and depth, and also a degree of sophistication that delighted an audience that in some cases tuned in just for him.

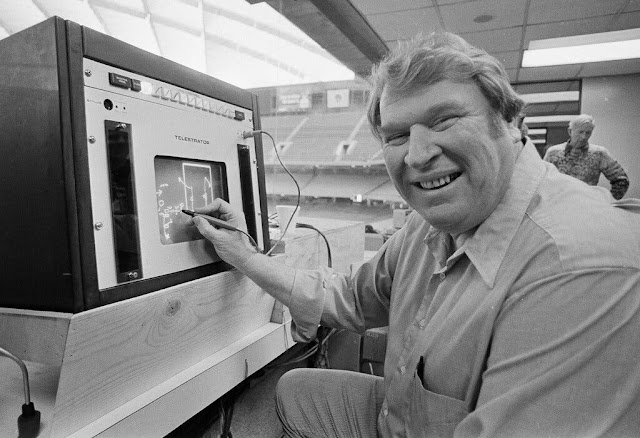

Fastidious in his preparation, Madden introduced what is now a standard exercise in the craft — observing practices, studying game film and interviewing coaches and players on Fridays and Saturdays. Come Sundays, he would distill that information into bursts of animated, cogent and often prescient analysis, diagraming plays with a Telestrator, an electronic stylus (whose scribbles and squiggles reflected its handler’s often rumpled appearance) that showed why which players went where."

...

Madden spent his first 15 years in broadcasting at CBS, starting in 1979. There he introduced his Thanksgiving tradition of bestowing a turducken — a turkey stuffed with duck stuffed with chicken — to the winning team. But the three other major networks all came to employ him because, at one point or another, they all needed him.

...

At his core, though, Madden was a coach and by extension a teacher; as he proudly noted in interviews, he graduated with a master’s degree in physical education, a few credits short of a doctorate, from California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo. His unscripted manner translated as well in the Raiders’ locker room — where he guided a cast of self-styled outlaws and misfits to eight playoff appearances in 10 seasons as head coach — as it did in living rooms, man caves and bookstores.

...

As inclusive as he was beloved, Madden embodied a rare breed of sports personality. He could relate to the plumber in Pennsylvania or the custodian in Kentucky — or the cameramen on his broadcast crew — because he viewed himself, at bottom, as an ordinary guy who just happened to know a lot about football. Grounded by an incapacitating fear of flying, he met many of his fans while crisscrossing the country, first in Amtrak trains and then in his Madden Cruiser, a decked-out motor coach that was a rare luxurious concession for a man whose idea of a big night out, as detailed in his book “One Size Doesn’t Fit All” (1988), was wearing “a sweatsuit and sneakers to a real Mexican restaurant for nachos and a chile Colorado.”

New York Times - "John Madden, America’s Broadcasting Gourmand, Ate Football Up"

"Madden was light years better as a commentator and entertainer than the many analysts who preceded him; it seemed he was calling a different sport altogether. His predecessors in the booth were slower to parse a pass or run and rarely first-guessed plays as deftly as Madden did. The best analysts today — Cris Collinsworth (who replaced him on NBC), Tony Romo and Troy Aikman — aren’t nearly as engaging or amusing.

One benefit of Madden’s highly informed, unpolished, Everyman appeal was his ability to keep viewers watching, or awake, during a blowout. Much of that was Madden — he would have been peerless beside nearly any other play-by-play announcer. But his relationship with his broadcast partner, the terse ex-player Pat Summerall, was part of the magic. Summerall set Madden up like an expert straight man, Bud Abbott to Madden’s Lou Costello."

"Madden was light years better as a commentator and entertainer than the many analysts who preceded him; it seemed he was calling a different sport altogether. His predecessors in the booth were slower to parse a pass or run and rarely first-guessed plays as deftly as Madden did. The best analysts today — Cris Collinsworth (who replaced him on NBC), Tony Romo and Troy Aikman — aren’t nearly as engaging or amusing.

One benefit of Madden’s highly informed, unpolished, Everyman appeal was his ability to keep viewers watching, or awake, during a blowout. Much of that was Madden — he would have been peerless beside nearly any other play-by-play announcer. But his relationship with his broadcast partner, the terse ex-player Pat Summerall, was part of the magic. Summerall set Madden up like an expert straight man, Bud Abbott to Madden’s Lou Costello."

New York Times - "How John Madden Became the ‘Larger-Than-Life’ Face of a Gaming Empire"

"Because of the limits of computer processing power, Hawkins, who had founded the gaming company Electronic Arts two years earlier, floated the idea of a video game with seven-on-seven football, rather than the 11-on-11 version used in the N.F.L. Madden just stared at him, and said “that isn’t really football,” Hawkins recalled. He had to agree.

“If it was going to be me and going to be pro football, it had to have 22 guys on the screen,” Madden once told ESPN. “If we couldn’t have that, we couldn’t have a game.

The extra years spent developing a more realistic game, which was called John Madden Football and debuted in 1988 for the Apple II computer, paid off. Decades later, the Madden NFL series of video games continues to sell millions of copies annually, has helped turn E.A. into one of the world’s most prominent gaming companies and has left a lasting mark on football fandom and the N.F.L.”

...

From the start, he insisted on realism, instructing developers on details as exacting as how a defensive player should be tackling and which stances linemen should use during certain formations.

The early interaction on the train — Madden had a lifelong fear of flying — showed Hawkins that Madden, despite being affable and entertaining, treated the development process seriously.

“Whatever John says is the final word. He had that kind of presence and the ability to be the commander,” Hawkins said. “It didn’t matter that I was running my company, he’s still going to tell me what to do,” he added with a laugh.

...

Madden’s desire to make the game as accurate as possible came even as he realized the real sport he loved did not always match how other people made their own fun.

“I went crazy one time, in fact, when my son Joe and Michael Frank played,” Madden told Grantland in 2012. “They were on the bus, and the score was 98-96. Neither one of them ever punted. It would be like fourth-and-20, and they’d go for it. I was so pissed off. I said, ‘You’ve got to punt.’ And they never wanted to punt.”

Still, he hoped the video game would help everyday fans learn the intricacies of football plays and more fully enjoy the sport.

Madden peppered the game development process with teachable moments. Once, at Madden’s house, Hawkins teased Madden for never delivering a playbook with 150 plays that could be used in the game, as was required in his contract.

“He basically pulled a 1980 Raiders playbook off a shelf and handed it to me and said, ‘Here you go,’” Hawkins recalled. “‘Here’s the playbook, you go figure it out.’”

"Because of the limits of computer processing power, Hawkins, who had founded the gaming company Electronic Arts two years earlier, floated the idea of a video game with seven-on-seven football, rather than the 11-on-11 version used in the N.F.L. Madden just stared at him, and said “that isn’t really football,” Hawkins recalled. He had to agree.

“If it was going to be me and going to be pro football, it had to have 22 guys on the screen,” Madden once told ESPN. “If we couldn’t have that, we couldn’t have a game.

The extra years spent developing a more realistic game, which was called John Madden Football and debuted in 1988 for the Apple II computer, paid off. Decades later, the Madden NFL series of video games continues to sell millions of copies annually, has helped turn E.A. into one of the world’s most prominent gaming companies and has left a lasting mark on football fandom and the N.F.L.”

...

From the start, he insisted on realism, instructing developers on details as exacting as how a defensive player should be tackling and which stances linemen should use during certain formations.

The early interaction on the train — Madden had a lifelong fear of flying — showed Hawkins that Madden, despite being affable and entertaining, treated the development process seriously.

“Whatever John says is the final word. He had that kind of presence and the ability to be the commander,” Hawkins said. “It didn’t matter that I was running my company, he’s still going to tell me what to do,” he added with a laugh.

...

Madden’s desire to make the game as accurate as possible came even as he realized the real sport he loved did not always match how other people made their own fun.

“I went crazy one time, in fact, when my son Joe and Michael Frank played,” Madden told Grantland in 2012. “They were on the bus, and the score was 98-96. Neither one of them ever punted. It would be like fourth-and-20, and they’d go for it. I was so pissed off. I said, ‘You’ve got to punt.’ And they never wanted to punt.”

Still, he hoped the video game would help everyday fans learn the intricacies of football plays and more fully enjoy the sport.

Madden peppered the game development process with teachable moments. Once, at Madden’s house, Hawkins teased Madden for never delivering a playbook with 150 plays that could be used in the game, as was required in his contract.

“He basically pulled a 1980 Raiders playbook off a shelf and handed it to me and said, ‘Here you go,’” Hawkins recalled. “‘Here’s the playbook, you go figure it out.’”

No comments:

Post a Comment